Eno Sarris has departed from Fangraphs. One of my favorite writers in the industry was a dream interview of mine and I spoke with him twice (one; two). He is an inspiration for how I’ve adapted as a writer in this space, taking a clever approach to analysis… and music. [Jay’s Note: And he really knows his beers. Like, more than we all think. He actually filled the hotel bathtub with ice and microbrews and was the beer sommelier the whole night at a Spring Training party with Grey and other industry peeps. I’d say I smelled his hair when he wasn’t looking, but his hair is OMNIPRESENT. If you’re in a 100-foot radius you can’t help but run into it…]

Prior to any of his chats on Fangraphs, he would a link to a song; good, bad, weird, or confusing, your taste didn’t matter. It was there for you to consume. While I won’t do this religiously as the 2018 season nears, for I question where my musical taste falls among our audience of readers, when opportunity presents itself, I act.

The 2018 Razzball Commenter Leagues are now open! Free to join with prizes! All the exclamation points!

Trevor Bauer likes the metal band Amon Amarth. Eclectic nordic metal from Sweden isn’t something you hear in clubhouses often. As you can imagine, the band has names you can find slapped on SKUs at your local IKEA: Johan Hegg, Olavi Mikkonen, Johan Soderberg, and Ted Lundstrom (add those sideways colon things where appropriate). Bauer’s ears enjoy growling vocals and endless chugging; my respect level for the 6-foot-1 righty has gone through the roof.

Rudy’s auction values place Bauer as an SP3, ranked 31st and directly behind the love of my life, Luis Castillo. NFBC leagues since January 1 have Bauer going as the 53rd pitcher and 141st player overall (NFBC 15 team rankings), and when you factor in NFBC choosing not to separate SPs from RPs in their sorting – boo! – there is some agreement on his value.

Grey thinks otherwise. And although he submits it might bite him in the arse, ranking him19th in his top 20 pitchers translates to eighth-round value when looking at Grey’s big board.

I’ll start high level and turn towards the granular aspects of Bauer’s game.

Grey’s projection – 15 W, 10 L, 3.59 ERA, 1.29 WHIP, 204 K, 189 IP

Razzball’s projection – 12 W, 9 L, 4.17 ERA, 1.31 WHIP, 174 K, 175 IP

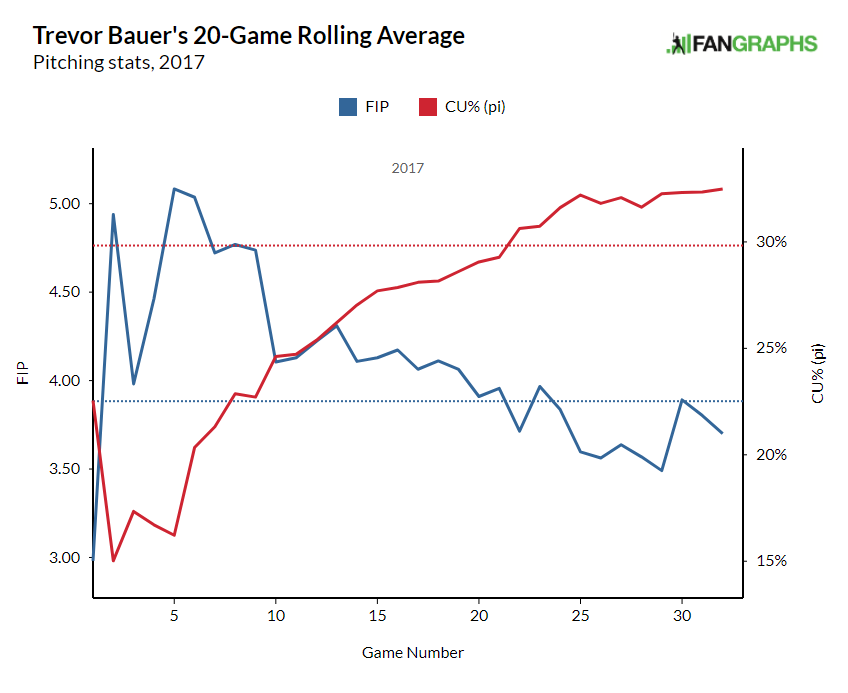

Now for the change which Grey mentions in his top 20 starters post, let’s take a look at Bauer’s 20-game rolling FIP plotted with his curveball usage…

(Thanks, Fangraphs!)

A tale of two halves, as with many arms, is an apt term for Bauer’s 2018. You’ll hear often that a full season is more predictive than individual stretches of a player’s year. This holds true, but if you can buy in to what a player changed, how he changed it, and the result, you can gauge the “stickiness” of that change and gamble on extended results.

With Bauer, he contributed to the offspeed pitch revolution that has been overshadowed by its brothers, Launch Angle and Juiced Ball. I immediately thought two things upon the discovery of elevated curveball usage: 1) did the pitch itself change and 2) how did it affect his other pitches.

Nummer Ett (“number one” in Swedish!)

You’re damn right I watched this one minute video on how to count to ten in Swedish!

It’s probably fair to assume any pitch changes when it becomes a component of a performance boost. Bauer’s curveball isn’t too different and innovators in the pitching biomechanics space, Driveline, may have been the reason why.

If you ever watch a start of Bauer’s, or one of most pitchers with a good curveball, you’ll notice the pitch can change depending on the count. The easiest way to think about this is with two buckets: get me over (early in the count) and put away (two strikes). According to Bauer himself, as linked above, he tinkered with the spin on his curveball by moving his index finger so it didn’t interfere with the spin axis of the ball. This allowed for a higher spin-rate curve thrown later in counts and studies have shown higher spin rate on breaking balls can increase the rate of a whiff.

Combing through Brooks Baseball shows us that the vertical movement of the pitch downward increased slightly as the season went on, and Bauer’s vertical release point of the pitch fluctuated as well. The former makes sense. More spin leads to a higher whiff rate, more spin and more whiffs likely means the pitch is breaking more than its former self. The latter, Bauer’s release point, could have to do with his index finger movement, but could just as easily be a feel-based, unconscious adjustment, or simply noise.

Splitting Bauer’s season into halves around August 1 shows his curveball’s refinement (August 1 is when Bauer’s curveball usage began to stabilize above his average usage throughout the whole season). Bauer’s glaring problem had always been neutralizing lefties. Compounding the above factors with location improvement – which we’re about to see – further solidifies not only how the pitch itself changed, but the resulting effects of this change, and his improvement. In the gif below, the small brown dot at the bottom of the zone is Bauer’s curveball location to left-handed hitters, improvement from the larger brown mass that covers nearly the whole plate, aka inconsistent.

Nummer Två

I am confident this the first time Razzball readers have seen the letter “a” with a dot above it.

I am not confident, however, that I’ll be able to isolate how Bauer’s changing curveball affects his other pitches merely because of the variables in place. High-level, one can say the increase in curveball usage made Bauer use his other pitches less; something had to move down in frequency to compensate for 30 percent use of his hook.

While Bauer began to abandon his sinker as the season went on, another big change for Bauer was using a slider over his cutter. This flip has been detailed well by others, but a sneaky difference with this alteration is the tier of velocity his slider falls into, allowing him to seamlessly change speeds between a 94 mph (fastball), 84 mph (slider), 78 mph (curve), and 87 (change). His cutter’s velocity used to sit 86-87 mph, close to his changeup, and even though the pitch’s movement is inherently different, from a timing perspective it was similar to another pitch of his. Even as I don’t have any hard evidence to back up a wider band of velocity helping Bauer out, further diversification of his portfolio of pitches in this manner feels like a win for the righty.

This slider was used 25 percent of the time when Bauer was ahead against right-handed hitters past August 1, and even though his sinker was widely non-existent, it peers its head when Bauer is ahead in the count. This effectively creates four options for a punchout against right-handed hitters, each of which is an improving or proven pitch. This is one reason why I side with Grey in projecting Bauer’s strikeout percentage to linger over the 9 K/9 mark, even if all else fails.

Conclusion

Not only did Bauer’s effectiveness versus left-handed hitters rise from the ashes, but his foresight to alter another aspect of his repertoire to further thawart right-handed hitters causes me to consider a world where the duo of changes results in even further strides towards prolonged success.

We now know a few important things about Bauer: he used his improved curveball more, he flipped from a cutter to a slider, and he listens to Amon Amarth.

14 W, 9 L, 3.85 ERA, 1.25 WHIP, 185 K, 170 IP, with upside, is my projection for Bauer.

I’m comfortable taking him as my SP3, right around the 12th round in a rotisserie league. This is the balance between Grey’s optimism and Steamer’s pessimism.

‘Til next time, my friends.

Amon Amarth is from Sweden. I am from Twitter.

You can follow Lance on Twitter at @LanceBrozdow!