I become obsessed with things. Sometimes it can be a particular food or an album (this Jimi Hendrix “vault cleaning” as Rolling Stone describes currently has my ear). Other times, as my mind is often tuned to baseball topics, I incessantly think about a concept from the diamond or evolution of a new statistic. Pitch tunneling is the recent topic earning a spot in my head.

This isn’t the first time I’ve gravitated towards pitch tunneling. Last year I wrote a column about Dylan Bundy’s cutter-slider, it’s usage, and why that pitch is one reason I irrationally like his volatile arm. As I’ve rekindled my interest in the concept, it was time for a refresh after Baseball Prospectus’ recent update. My motive was simple: combining what we know about a pitcher and what we can learn from tunneling might provide us with reasons for optimism.

I’ll admit, this post might get a little bit convoluted, so if you’re not in the mood to try and understand pitch tunneling and determine how much you value it, feel free to hop to one of my last three Razz articles – there’s something for everybody (On Scott Kingery; On ADP discrepancy; On Michael Wacha). Or just skip down to the heading for Patrick Corbin. I’ll try my best to keep things as simple and concise as possible. Teaching a concept is often a great form of learning, so I’ll admit that writing this post, in a way, helps me to understand the topic and its associated statistics better.

Primer

Tunneling as a whole is built around the concept of a tunnel point. This is the point at which the decision to swing must be made. Anything decision made late and your chances of catching up to a pitch are zero. In theory, if a pitch moves substantially after this point, then the chances one makes contact, of any quality, decrease. This occurs because the human eye doesn’t actually track the ball the whole way to the bat when one is hitting – the ball is moving too fast. Therefore, a batter must make a decision to swing at a time when the final point of the ball is unknown, implying there is some prediction of where the ball will be, and thus, where one must swing. More movement after the tunnel point, as far as we know, is a precursor for more whiffs. In layman’s terms, this is essentially “late life” on a pitch.

Stats for pitch tunneling can be broken down at the pitcher level and the individual pitch combination level, each of which have their own merits. Most of the time, you’ll see photos of a pitch visualizer (which we’ll see below) showing all of a pitcher’s pitches and their trajectory relative to one another. This gives you a great idea of how a pitcher tunnels all of his pitches together.

You can also look at two pitches together in sequence and learn how they interact and the results they produce. Ideally, a pitcher wants as little difference as possible at the tunnel point between two pitches that end up at two different locations at home plate. Think about all the gifs you see about devastating changeups; each of those are considered “good” because they look like a fastball until the last second. I like focusing on pitch combinations because most of the time, to one handedness of hitter, a pitcher has a pair that makes up 60-75 percent of what a hitter will see in the aggregate. While I won’t differentiate for sequencing – whether a pitcher goes fastball-changeup or changeup-fastball – we can still gain some information by focusing combination with greater frequency: the offspeed pitch coming after the fastball.

For this dive, the two pitch combinations I looked at were fastball-slider and fastball-changeup. (Curveball tunneling is still a concept I want to refine my knowledge on.)

Here are the tunneling statistics I find most applicable for analyzing pitchers. I’m renaming two of them as I think the current names given confuse more than they inform. These metrics are discussed at length by Baseball Prospectus and the full table of their stats, in all their glory, can be found here.

- Movement ratio – what percentage of a pitcher’s difference in plate location between two pitches comes from movement after the tunnel point.

- Average is 11.9. Higher is presumed to be better.

- Tunnel distance – max distance between back-to-back pitches at the tunnel point.

- Average is 1.54 inches. Lower is presumed to be better.

- Release distance – how far apart two pitches are upon release.

- Average is 2.6 inches. Lower is presumed to be better.

Now, let’s back our way into two interesting arms using our basic knowledge of pitching tunneling. It may seem excessive to detail all this and only cover two pitchers, but I hope to use this column as a reference for further discussion about pitch tunneling and how it relates to pitcher analysis for fantasy baseball.

Corbin is quietly coming off a decent season, posting a .408 FIP over 190 innings in a hitters ballpark. He slotted in as a top-200 player, just falling inside SP4 territory, continuing his ability to neutralize left-handed bats with a 3.18 FIP against and sub-.220 average against. We know he can stymie lefties, but the missing piece, as it is for so many southpaws, is finding a way to beat right-handed hitters.

One of the talents Corbin has is his ability to create late movement when he sequences his four-seamer and slider to right-handed hitters. This specific combination has the second highest movement ratio (definition above) among pitchers with 75 or more sequences of a four-seamer and slider (17.6). He sits slightly above pitchers like Justin Verlander and Jacob deGrom on the metric, but what I noticed is that while this fastball-slider combo is his dominant sequence to right-handed hitters (174 instances), he opts for a sinker-slider combination a decent amount of the time (125 instances). This stood out because the disclosed tunneling metrics – including this movement ratio – are all better when he sequences his slider with his four-seamer rather than his sinker. Given this slider is clearly Corbin’s best pitch, intuition would suggest he would want to set up that pitch to make it even better.

Corbin’s used his sinker more than any pitch against right-handed hitters last season, yet this sequencing of his slider with his four-seamer seems to suggest there is some understanding that it’s better to set his slider up with his four-seamer. While I’m not a pitching coach willing to suggest Corbin should use his four-seamer more to right-handed hitters, the application of this to fantasy would be keeping an eye on Corbin early and seeing if there is any increased usage of his four-seamer to righties. If so, I wouldn’t be stunned to see his slider improve, his strikeouts increase to above 9 K/9 and for his one weakness – right-handed hitters – to be relatively neutralized. Given his four-seamer has been more successful than his sinker against right-handed hitters and it seems to set up his slider better, there may be a path to him turning around his struggles.

Corbin is currently going 227th overall in NFBC leagues, the 87th pitcher off the bard (relievers included). We at Razzball have him right in that same window, but I’m tempted to jump on him slightly earlier to fill out my staff given what I’m seeing here. Here’s a decent look at his Corbin’s slider, with a suggestion from fellow fantasy writer Van Lee (Fantrax) related to the one factor I didn’t touch on: Corbin’s slider was better outside of Chase Field and we all know about the humidor.

This is Patrick Corbin's slider outside of Arizona last year. Now imagine it doing that every time in the *new* Chase Field pic.twitter.com/dntwzR2iAs

— Bootu Inc. (@BootuInc) February 14, 2018

Jon Lester

If you’re using Rudy’s WAR room – and you should be – then you’ll see Lester popping up as a good value in leagues around 100 overall. We at Razzball have him ranked right in the ninth round, 17 spots ahead of where NFBC leagues are seeing him leave boards. Despite an underwhelming performance last season his peripherals look pretty stable and if you can get past his age, there is some value to be had. This is especially true if you believe in his ability to tunnel pitches and repeat his delivery exceptionally well.

Lester stands out in tunneling metrics when you look at his aggregate pitch tunneling among all his pitches to hitters (as opposed to what we looked at with one combination for Corbin above). Among pitchers with more than 1,000 pitches, Lester has the lowest difference in release distance compared to 161 other pitchers (see above) at only 1.54 inches. Said frankly, everything Lester throws comes out of his hand from a similar spot more than any other pitcher in baseball. This nearly eliminates the ability for hitters to pick up what Lester might be throwing upon his release, leaving them at the mercy of other queues to pick up on in a shorter amount of time.

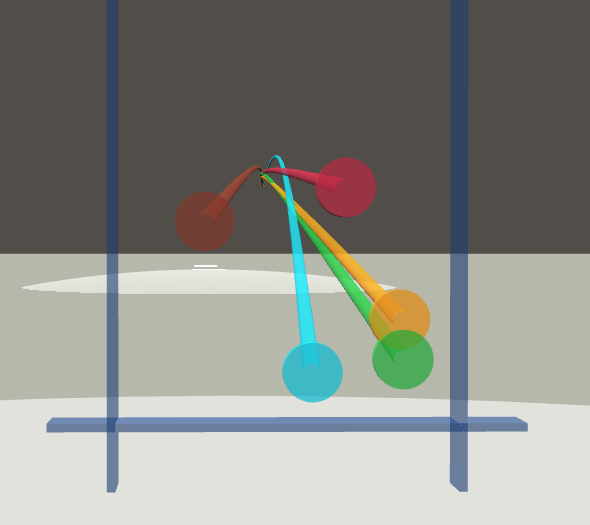

Below is a screenshot of Lester’s pitches only to right-handed hitters. A really good visual of tunneling is looking at Lester’s ability to make multiple pitches come out of a centralized point (follow this link to play around with the tool I am using to generate these shots). While you might suggest it’s easy to pick out which pitch is which based on its intended direction, understand that you’re doing so with a still frame. The time between separation of those pitches and the decision to swing is extremely small. Lester does an amazing job of taking away any advantage a hitter might have before this point.

Four-seamer (red), Cutter (brown), Curveball (blue), Sinker (orange), Changeup (green)

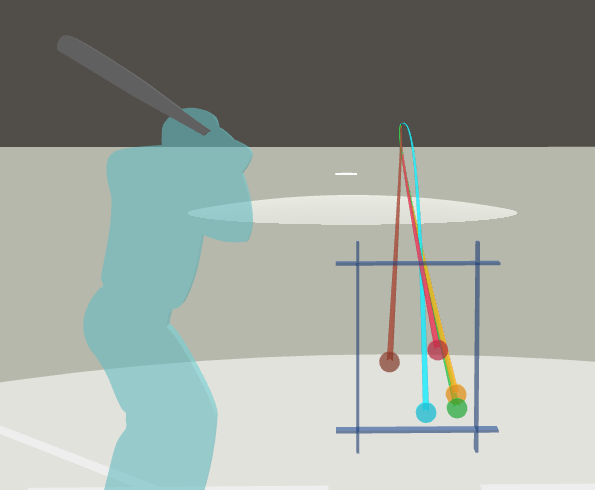

Here is another picture of the above shot from a different angle.

This angle gives you a better idea of what things look like out of Lester’s hand from the eye level of a hitter as opposed to putting a GoPro in a catcher’s mitt, like the image above. While Lester’s curveball stands out, it’s the meshing of his other four pitches which seamlessly blend together.

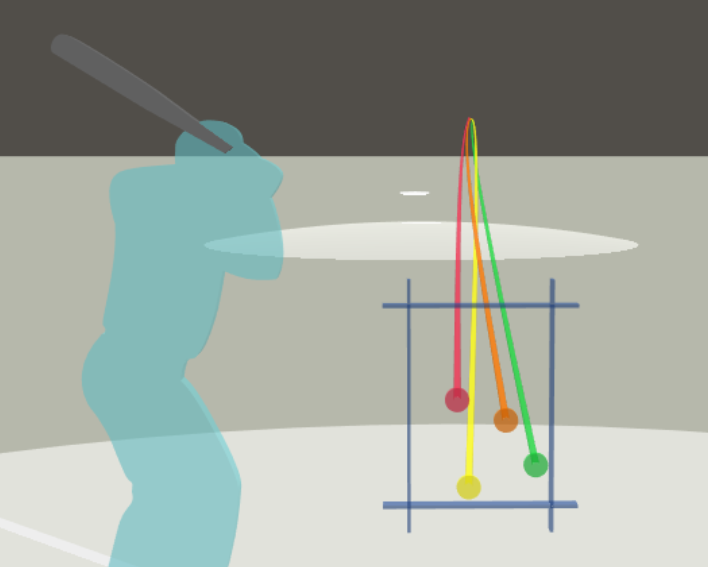

To give you an idea of what an average pitcher looks like from this perspective, let’s actually look at Corbin’s pitches in the aggregate, who as a whole – removing his fastball-slider tunneling – is an average “tunneler.”

Comparing the two pictures, it’s easy to see how each pitch’s average path is distinguishable, whereas with Lester, the deviation happens much later.

One thing we know about Lester is he’s one of a small crop of starters projected for under a 4.00 ERA by Steamer, even with the context of his age. I also want to point out that in the age of believing innings are everything, Lester has thrown 180 or more innings every year since 2008 – ten years in a row. The polish Lester has on his mechanics is better than any pitcher in baseball, remaining an elusive reason for this prolonged durability. That repeatability translates into tunneling, creating what I believe to be a fantastic floor, even for a 34-year-old. If you’re considering drafting Madison Bumgarner at his current price tag of 27th overall, I would suggest a long, hard look at waiting roughly 100 picks and grabbing Lester instead. Tunneling is just one reason

Tunnel your way to Twitter and follow me.

BigThreeSports is where my personal fantasy rankings will be housed… but really just listen to Rudy’s…