I am bringing back an oldie-but-goodie for this week. Pitcher Thoughts was initially a Razzball column idea that I periodically spun-off into a subset of my podcast (I do another one with Ralph too!). My intention was to give readers more information about a pitcher’s performance (or lack thereof) past the simple baselining of FIP versus ERA and the standard jargon. I’m a sucker for pitch mix and predicting what might change and why. This also allowed me to gain an understanding of a specific pitcher far deeper than I would otherwise considered. A mutually beneficial column is always good. It’s a no-brainer that another iteration was necessary. Our pair for today is Mariners southpaw, Marco Gonzales, and Brewers righty, Chase Anderson.

I traded emails with a former independent-league pitcher, Dan Blewett, regarding Michael Wacha tinkering with his curveball sequencing earlier this season. His words that resonated most with me bluntly stated that even at 27 years old (Wacha’s age), pitchers are still learning how to pitch. Marco Gonzales, 26, is a fantastic example of this.

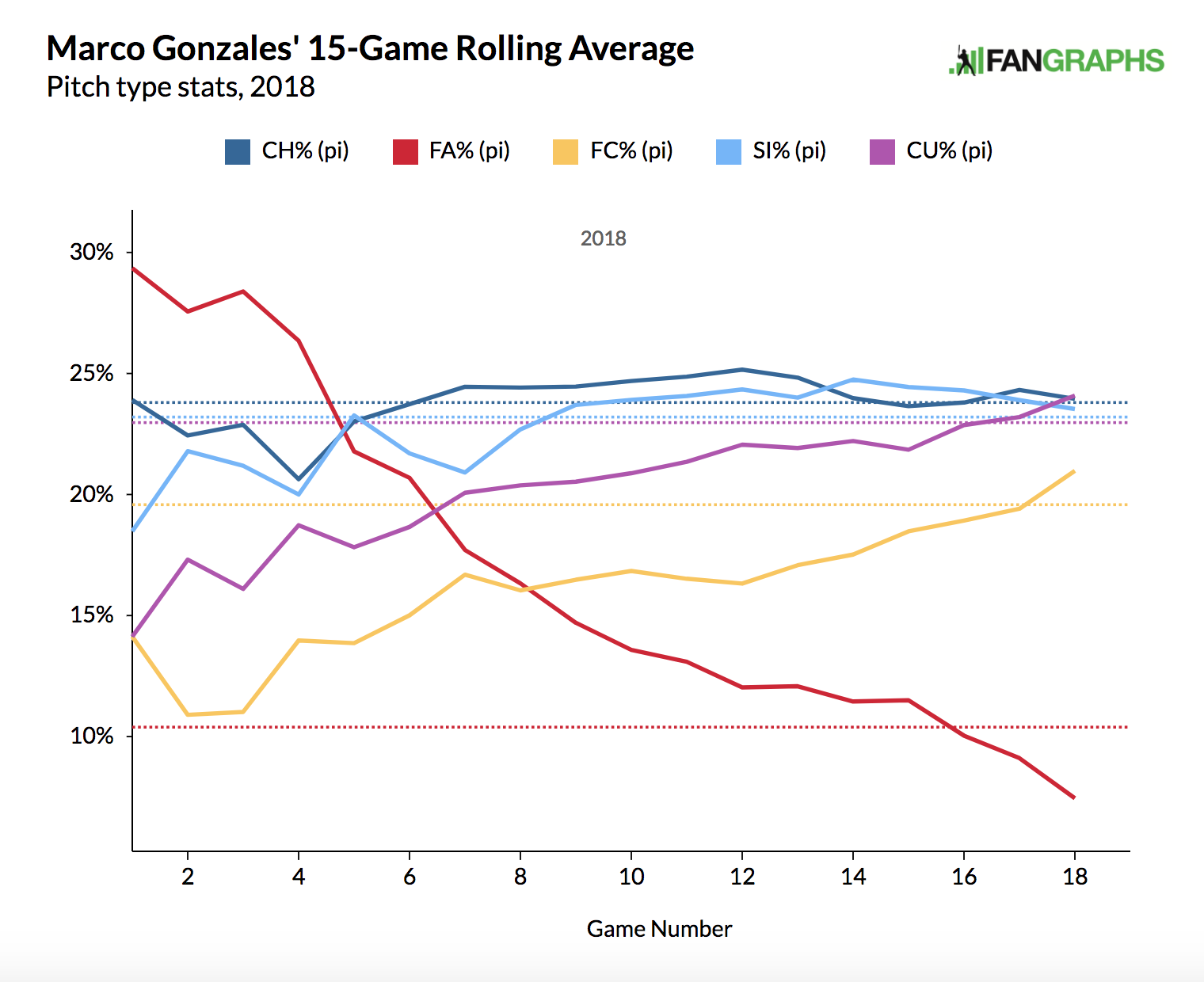

Compare his pitch usage last season and early in 2018 to the present version of Gonzales and you’ll see a very different pitcher.

The hard, red line cutting through the graph above is Gonzales’ four-seam fastball, a pitch once featured over 50 percent of the time (2017) that’s now sparingly used. As a consequence of this, Gonzales has favored his cutter and sinker to replace his fastball and elevated the usage of his curveball to make sure he is doing what everybody else in baseball is doing (kidding… but seriously). The result has been a 3.34 FIP through 106 1/3 innings compared to a 3.64 ERA. A lower FIP than ERA for a pitcher with strikeout numbers right at the league median among starting pitchers is impressive given FIP’s focus on strikeouts. Gonzales’ control is the main reason his FIP isn’t in another stratosphere and it’s actually improved from above average to nearly the best in the league on walk percentage alone (85th percentile).

Understand why the Player Rater doesn’t look fondly on the southpaw is not too complex. For one, we’re working with a small sample of performance with a very different pitch mix. In that, there is both uncertainty in how Gonzales’ mix sustains over time, and more importantly, how hitters begin to react to his trickery. This non-statistical explanation of why projections might be lower than expected even with good results and peripherals can apply to nearly any young pitcher.

Gonzales is unique in his success against left-handed hitters not extending to the point of dominance. He’s faced nearly 85 percent right-handed hitters this season, up from the prior year. Gonzales’ splits, however, aren’t indicative of the fear some left-handers like Chris Sale put into managers when lineup construction rolls around. He holds only about a 20 point wOBA differential between handedness of hitters and actually strikes out more righties than lefties on average.

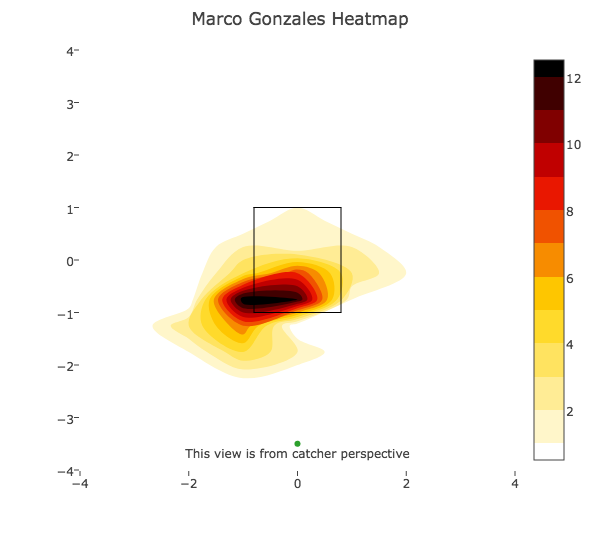

This suggests his curveball – the pitch that naturally trails away from left-handed hitters – might not be deceptive enough to create an above-average whiff rate versus lefties or even hitters in general. When looking at his PitchFX data on Baseball Prospectus, we can confirm his bottom quarter curveball whiff rate and slightly above average horizontal and vertical movement. The pitch isn’t difficult to make contact with for hitters, but it’s effective because it’s really hard to get in the air (top three curveball ground-ball rate among left-handed pitchers, min. 100 pitches). This comes back to Gonzales’ location on the pitch, which he maintains really well at the bottom third of the zone in two-strike counts.

Marco Gonzales curveball location in two-strike counts to RHH (2018).

Command a pitch that doesn’t stand out on movement or spin leaderboards and you can quietly make it effective.

Gonzales is a control-based pitcher who feels like he’ll always struggle to generate an appealing amount of whiffs with the current movement on his offspeed pitches. Hitters are bound to adjust against his cutter-sinker preference over his four-seamer, but his command might limit how successful the adjustments can be. He feels like a high floor, low ceiling option in most deep leagues; a pitcher most should consider streaming when the matchup is right. If Gonzales tinkers with his offspeed, there could be more growth in the tank.

While Gonzales faded his four-seam usage for more sinkers and cutters, Chase Anderson has favored the harder sibling of the sinker. Since 2017, Anderson’s four-seam usage has been steadily increasing to its current clip above 35 percent. On the downswing since is the usage of his sinker and cutter, now both below 15 percent. In the process, his offspeed usage has been stable.

Coming into 2018, Anderson had a tough track record to trust, but reason for others to buy in. His late push at the end of 2017 fit him into the recency bias bucket of late-season production hopefully carrying over into the subsequent year. That unfortunately was not the case.

Anderson posted a 5.63 FIP in the month of May, making him a droppable commodity as his strikeouts ticked below 18 percent. June brought with it league average performance, with a FIP north or 4 but strikeouts that slowly creeped back into the picture. The issue in Anderson’s first few months of the season seems to stem from his changeup and sinker, the latter struggle possibly a valid reason for his increase four-seam usage.

Oddly enough, Anderson’s changeup is above the 90th percentile among right-handed pitchers for both horizontal and vertical movement. With a 10 mph velocity differential off his fastball, it’s hard to believe this pitch is near the bottom quarter of all changeups in whiff rate for right-handers given everything we know about changeups. The enigma continues when you realize his location of the pitch to left-handed hitters – whom he predominantly uses the pitch against – is right on the black. So we’re left wondering whether Anderson’s sequencing of the pitch might simply me poor. It does look like he blankets usage of his pitches across counts, with no real pattern. For a pitch as finicky as a changeup, this could be part of the issue, especially if his tunneling of the pitch has deviated from the success it brought last year.

Unfortunately for Anderson, his changeup might not even be the worst of his worries. His home run rate versus right-handed hitters churns most stomachs and his home run to fly ball rate doesn’t suggest regression back to earth might only be minimal in the second half.

Anderson is more of an enigma to me than Gonzales. With Gonzales, we kind of know what we’re getting on a start-to-start basis. With Anderson, I’m left salivating over the movement, location and velocity characteristics of his changeup, only to realize the pitch isn’t as successful as it was last year. The sustainability of his curveball has allowed for some success recently, but his cutter remains borderline unusable and it remains to be seen whether relying on his fastball at an elevated rate simply makes teeing off on him easier as he veers away from his naturally grounded sinker. Anderson has some aspects of his game that are very intriguing, but with worrisome components that the majority of other pitchers have already figured out, I’m inclined to think there is hope, but it will require admirable fortitude to grind through the rough patches.

Always thinking about pitchers on Twitter – @LanceBrozdow

Do you like MacKenzie Gore? (The answer is yes.)

Check out my conversation with him after his Independence Day dominance…