This is part two in what is a very special mini-series exploring the St. Louis Cardinals’ “Gas House Gang”. You can read part one here. The story continues…

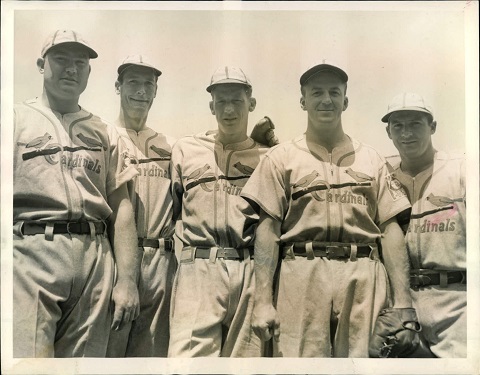

Left to right: Johnny Mize, Curt Davis, Lon Warneke, Terry Moore, and Joe Medwick.

Most of the starters were sick of the Deans. The favorite refrain, repeated endlessly over the course of the season, “Them Giants don’t have a pig’s chance in winter of beatin’ me and Paul.” Perhaps the pitcher who took the most offense at the braggadocio was Jean Otto “Tex” Carleton. Carleton, like Frisch, was a college grad. He had a naturally truculent disposition and was looking for trouble most of the time. He was deeply resentful of the Deans, predicting that they wouldn’t last in the Bigs.

“Wild Bill” Hallahan was another pitcher, a southpaw, who had a tense relationship with the Dean Brothers. He had several outstanding seasons with the Cardinals, especially the 1931 World Championship season; he was 19-9 with a 3.29 ERA that year, leading the league in both wins and strikeouts. He pitched brilliantly in the World Series against the formidable Philadelphia A’s, winning both games he pitched and giving up but one earned run in 18 innings. However, he had an off year in ’34, ultimately pitching to an 8-12 record, and Dizzy was always resentful of the comparatively higher salary Wild Bill made in comparison to he and his brother. In Dizzy’s mind, it was the Dean’s who were doing all the heavy lifting that year, and, of course, there was a great deal of truth in that.

The other southpaw was Bill Walker, who quietly had a productive year, 12-4 with an ERA of 3.24.

There were two other pieces to the puzzle who actually did not take part in any of the verbal fireworks. First Baseman Rip Collins so enjoyed the game, and that immemorial season in particular, that he later stated, “I would have played for nothing.” And, then there was the catcher, Virgil “Spuds” Davis, a quiet, reserved individual who was always polite and just grateful to be on club. But, even Spuds fit in with the eccentric bunch; he often asked Dazzy to recite a Seminole prayer before he got up to bat.

The Gruff Drill Sergeant was Player/Manager Frankie Frisch, one of the greatest Second Basemen of all time. Although Dizzy was a problem child, the Flash actually had, perhaps, more serious issues dealing with the Sophisticates. During the World Series, Frisch, feeling exhausted, asked Durocher to stand a few feet closer to the 2nd base bag to cover for him. Durocher snickered at Frankie, asking Frisch if he wanted him to bring out a wheelchair for him; he was not going to leave an open area in the Shortstop hole so that The Fordham Flash would look good in the Series, and he, Durocher, would be the goat if a ball snuck through his coverage area. Several years later their smoldering animosity blazed into a physical conflagration.

The miraculous thing is that late in the season all three teams came together. As noted by John Heidenry, author of the marvelous work The Gas House Gang, “this coming together was not inevitable, in fact, it was against all odds.” But, it did happen, and that is why the Gas House Gang is a legendary team in baseball’s pantheon of heroes.

Ultimately, the glue that held all these men together was that — underneath all of the bickering, the blustering, the chaos, and, at times, outright insanity — there was a deadly seriousness of purpose. Baseball was not a way of life — it was life itself. The drive to win was just as intense for the hillbilly crowd as it was for Leo, “Nice guys finish Last”, Durocher.

In 1933 the nation was still suffering from the seemingly endless depression, and baseball was as well. Attendance had plummeted around the league and baseball salaries had dropped 25% in the previous four years. The National League owners discussed the desperate move of adding a 10th man in the lineup – a DH.

The nation needed not only an economic, but a social, recovery; much of it would be spurred on by the drama and entertainment provided in the coming year by the Gas House Gang. The exploits of that legendary squad would boost baseball into its golden age.

Actually, no one ever called the club the Gas House Gang during the ’34 season. There remains controversy over the origin of the term, as well as its meaning. Some claim that it was first mentioned by Leo Durocher during the 1934 World Series. More likely, the name was initially coined by sportswriter Joe Williams of the World-Telegram, who stated that the Cardinals “looked like a bunch of guys from the gas house district who had crossed the railroad tracks for a game of ball with the nice kids.” Thus, a Gas House Gang was a dated slang for a tough New York neighborhood. Although many of the same players were on the 1935 team, the name was never used in reference to that, or any other, Cardinal squad. And, quite an assemblage it was. The nicknames alone give an auger of the tale: Dizzy, Daffy, Ducky, Leo the Lip, the Wild Horse of the Osage, the Fordham Flash, Pepper, Tex, Wild Bill, Dazzy, Spuds, Rip, Whitey, and The Dashing Dago….

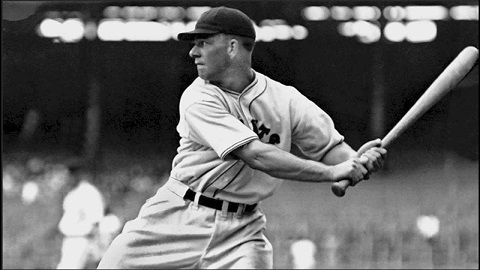

1926-47, Mel Ott, New York Giants

Although the Cardinals started off the season 3-7, they soon righted the ship and found themselves in first place by Memorial Day. After sweeping two games from the Phillies, and three from the Reds, their record was 25-13 on May 31; they had won 22 of their last 28 games. It was apparent by June that their main rivals for the pennant were the Giants and the Cubs, and that the New York Club, led by Hall of Fame player/manager Bill Terry, young star Mel Ott, Carl Hubbell (master of the screwball) were the favorites. In late June the Cardinals split a four-game series with the Giants and a week later did the same with the Cubs. The Cardinals were holding their own, 3 ½ games behind the Giants, but it was becoming apparent that the Cardinals’ starting pitching was weak outside of the Dean boys.

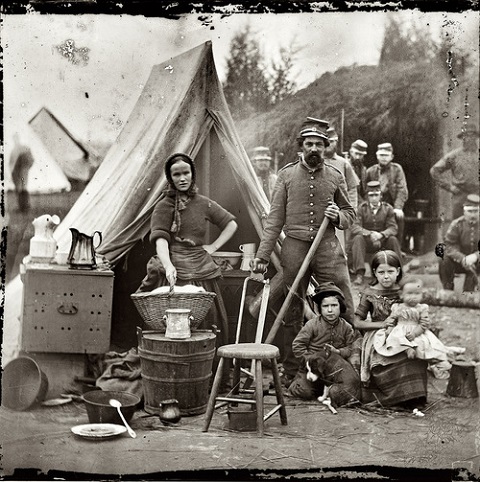

Migrants from Great American Dust Bowl

Then the heat of mid-season came and with it the Great Dust Bowl. In 1933 there had been 38 storms. By 1934 it was estimated that 100 million acres of farmland had lost all or most of the topsoil to the winds. Tons of soil were blown off barren fields and carried in storm clouds for hundreds of miles. There were fine layers of dust always settling at Sportsman’s Park in St. Louis, which at the time was the most western venue in the Major Leagues. The heat was brutal and constant. At one point, for 30 straight days, temperatures were 100 degrees or more. Even the most stolid umpires, such as Bill Klem, did the unthinkable and discarded their suits and called the game in short sleeves.

One day Dean built a fire in front of the Cards dugout. He then procured two blankets, stomped the earth, and let out blood-curdling war cries in between yips. He pantomimed rain coming down from the skies, took out an imaginary umbrella, and received applause as he returned to the dugout. As the season progressed, Dizzy was becoming larger than life, a living legend, a ballplayer possessed of almost mythic skills.

Despite having a winning record against the Giants, the Gang was still 6.5 games out of first place on August 1. They also trailed the 2nd place Cubs. By that point Frisch had almost given up on the remainder of his starters and was pitching the Dean Brothers on alternating days. At mid-August the Cardinals still trailed the Giants by 5.5 games and the Cubs by 3.5; there seemed little chance that they would get to the Series.

Now in those days, it was the practice of Major League ball clubs to often play exhibition games on their off days; this was especially important during the depression years, as the attendance had fallen off precipitously, and many teams were in danger of going bankrupt. Dizzy (and Paul) had snuck off the train heading to Detroit, where he was supposed to pitch an exhibition, feeling that he was overworked as it was (which was, of course, true.) They were then fined by management. Both Deans (Paul grudgingly) refused to pay the fine. When Frisch ordered them to go onto the field, and they refused, they were both suspended. At that point Diz ripped his uniform to shreds. What followed was the most outrageous rebellion in baseball up to that time; the Deans went on strike in mid-season for more pay, in the midst of the pennant race. Baseball had never seen anything like it. Dizzy threatened to retire from the game. Ultimately, however, Paul parted ways with his brother and accepted the fines. Commissioner Judge Landis, who was requested by Dean to arbitrate the matter, then ruled against Dizzy, who accepted the fine, payment for the shredded uniform, and suspension, which was lifted immediately, being in everyone’s best interest.

On September 16th the Cards swept the Giants in a key doubleheader, with Paul beating Hubbell. Paul had won 4 of 5 against the Giants, with the Cards 12 wins in total versus their main rivals. Paul would later pitch a no-hitter against Brooklyn. Dizzy’s boast that “Me ‘n Paul” would win 45 games actually fell modestly short of their actual total of 49 wins; the entire rest of the pitching staff won 45 games. Dizzy, despite missing several starts due to his “work-strike”, managed to win 30 games, against 7 losses. Paul himself won 19 regular season games.

The Giants had come into September with a seven-game lead. No team in Major League History up to that time had ever gone into the last month of the season with that sizable a lead and managed to lose the pennant. On September 21st the Cards had played a doubleheader against the Dodgers. Of course, the Dean duo was scheduled to pitch. Dizzy pitches a shut out, and Paul follows it up with a no-hitter. Dodger manager Casey Stengel lamented, “How would you feel? You get three itsy-bitsy hits off the big brother in the first game, and then you look around and there’s the little brother with biscuits from the same table to throw at you.”

With four games to go, the Giants maintain a two-game margin; their record is 93-56, while the Cardinals sit at 91-58. The Cardinals have a four-game set against the hapless Cincinnati Reds, who have the worst record in the Major Leagues. The Giants play two games against the Phillies, who are deep in the second division, and then finish out the season with two more at home against their biggest rivals, Casey Stengel’s Dodgers.

The Gas House Gang wins the first two games against Cincinnati, with Dizzy beating the Reds for his 29th win of the season. The Giants, continuing their desperate free fall, lost two straight to the toothless Phillies. Now they are tied. And, the drama increases. Sensing failure before the games are even played, Beat writer Garr Schumacher of the New York Evening Journal states, “Their collapse is a baseball story unlike anything in the annals of the game.”

Although Brooklyn has long been eliminated from the pennant race, the fans are still smoldering from a comment that Bill Terry had made in an interview that previous winter. When questioned as to whom he thought would pose the most dangerous challenge to the Giants pennant hopes, he replied, “Pittsburgh, St. Louis, and Chicago will be the teams we’ll have to beat,” Terry said. “I don’t think the Braves will do as well as they did last year.” When asked if he feared the Dodgers, Terry responded, “I was just wondering whether they were still in the league.”

Join us next week as the story concludes…